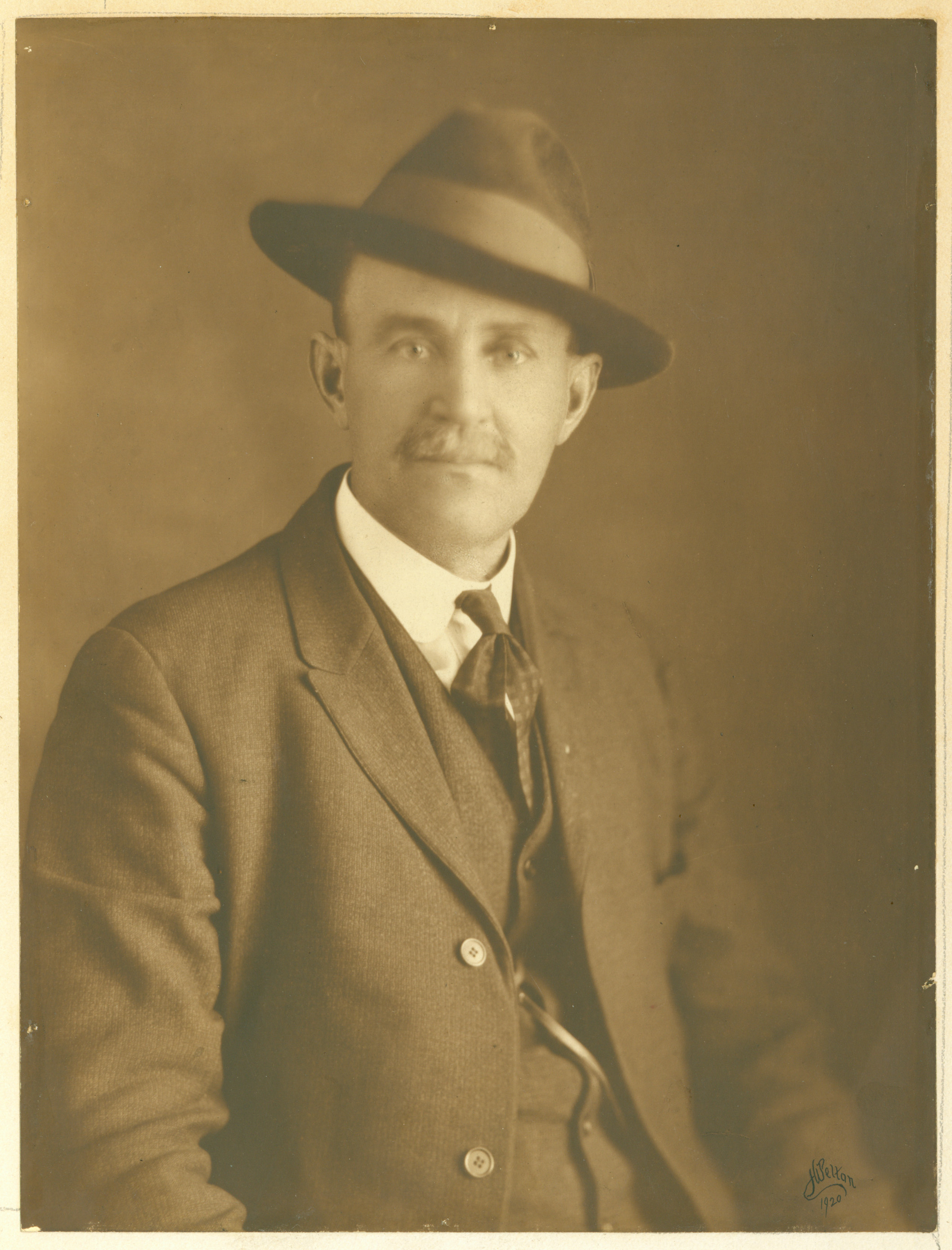

James Vester Miller was born just prior to the Civil War, on April 21, 1860 (according to his grave, although other sources cite 1858). His mother, Louisa Miller (1837-1902) was a native of Charleston and presumably enslaved at the time of Miller’s birth, according to the North Carolina Architects and Builders: A Biographical Dictionary website. On Miller’s death certificate his father was named as John Miller, a white man from Rutherford County. After Emancipation Louisa moved with her three sons from Rutherfordton, North Carolina, to Asheville.

As he grew Miller was known for his curiosity and driven work ethic. During this time the public school system had not been established in Asheville, and there were no educational opportunities for black children. Employment opportunities were limited as well. Miller hung around construction sites, doing odd jobs and working up to an apprenticeship learning the brick masons trade.

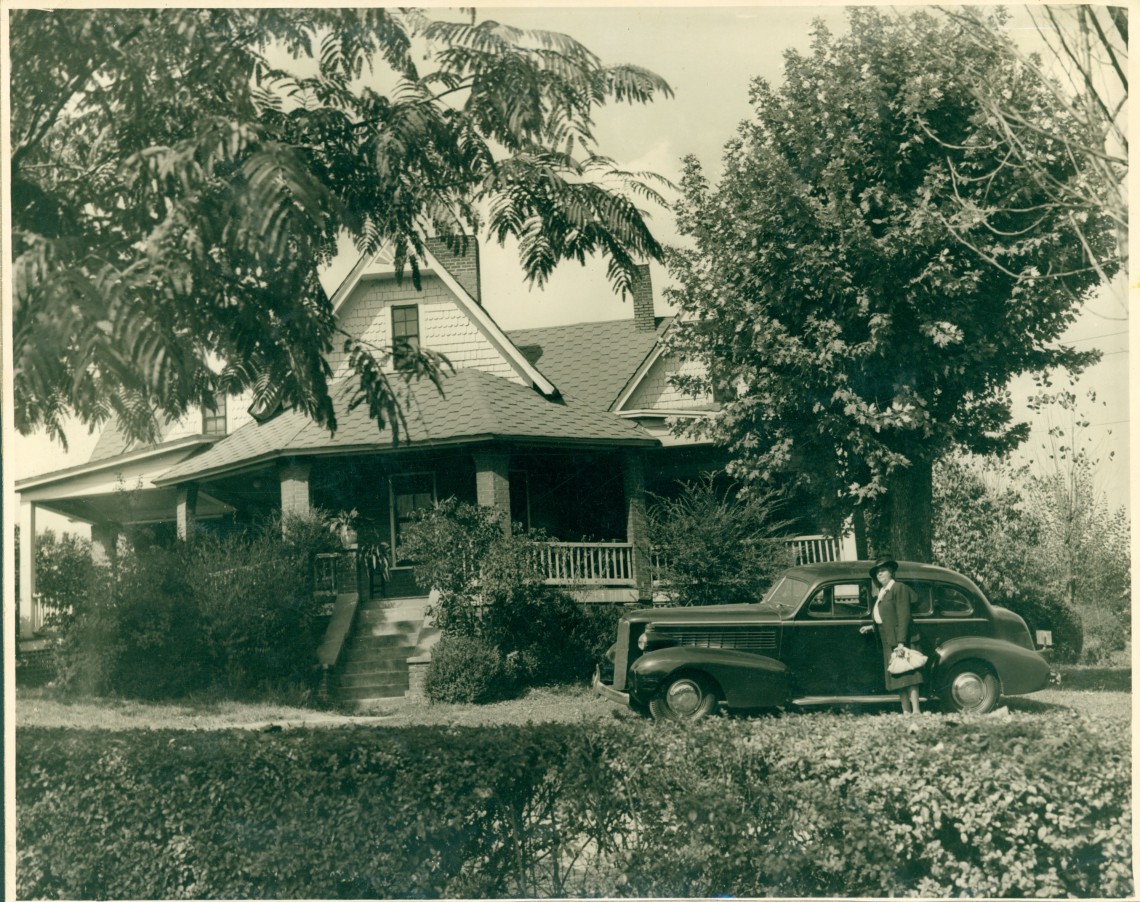

In 1881 James Vester Miller married Violet Agnes Jackson. The Miller’s had five sons and one girl. Four of the sons became Master Masons like their father, while one, Lee Otus, graduated from Boston University before returning to Asheville with his wife Daisy, as one of the first black physicians in the city. Miller built a 16 room house on Emma Road known as Out Home.

Miller also had three children with Ida Ruth Clark: Maggie Belle, James Howard, and Taft. According to Asheville City-Directories Ida lived at 138 Cumberland Avenue in 1902, where she was employed as a domestic and a cook. In 1907 she lived at 49 West Street in a home provided by Miller. Her son James Howard Clark was the father of Photographer Andrea Clark who has preserved and brought to light much of Miller’s legacy. A photograph in the NC Collection at Pack Library shows Ida and James in a studio portrait around the turn of the 20th century.

James Vester Miller worked for some of the city’s top contractors before starting his own business, Miller & Sons Construction. His firm specialized in churches and commercial buildings.

In addition to his contract work, Miller invested heavily in real estate, building 26 homes for rent or sale.

Buildings known to be constructed by Miller and his company are:

St. Matthias Episcopal Church

1 Dundee Street, Asheville

Believed to be the oldest African-American Congregation in Asheville, the original church was known as the Freedman’s Church and served as a place of worship and a parochial school. The present building was built in 1894 to replace the previous frame building. Today St. Matthias is still a thriving and diverse congregation. The building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

St. James AME

44 Hildebrand Street, Asheville

The St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church began its new building in 1917, and it was completed in 1930.

Hopkins Chapel

21 College Place, Asheville

In 1868, a few years after Emancipation, black members of the Central United Methodist Church founded their own temple, first by walking out of the Central church where they were treated as second class citizens, not children of God, and meeting under an arbor. They soon rented a schoolhouse and later built a small church on land at the site of College and Pine Streets. In 1907 the church that had been built by hand burnt down. The congregation moved worship to the YMI, then hired architect Richard Sharp Smith and brickmason James Vester Miller to construct a new brick church – dedicated in 1910.

Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church

47 Eagle Street, Asheville

Built in 1919 to house a growing congregation, Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church on Eagle Street continues to be a strong presence in the community and responsible for much of the progress and development on ‘The Block.’

YMI Cultural Center

20-44 Eagle Street, Asheville

Mr. Isaac Dickson and Dr. Edward Stephens approached George Vanderbilt in 1892 to provide an institution for the black construction workers employed at the Biltmore Estate “to improve the moral fiber of the black male through education focusing on social, cultural, business and religious life”. Richard Sharp Smith, supervising architect of the Biltmore estate, was the architect for the YMI Cultural Center that was financed in part by George Vanderbilt. In 1893, the YMI’s doors opened. In 1905 the YMI Board of Directors raised $10,000 in six months to purchase the building from Vanderbilt. According to the Asheville City Directory Miller and Sons had their offices in the YMI Building in 1917.

J.A.Wilson Building

13 Eagle Street

Built in 1924 by Miller Construction Company for J.A. Wilson, a black businessman who ran a barbershop in the building, and had an undertaking business across the street at 18 Eagle Street. According to the 1927 Asheville City Directory the building was a hub of African American business and professional life. Three doctors had offices there: Lee Otus Miller (James Vester Miller’s Son), John W. Walker, and Louis N. Gallego. Attorney Henry L. Alston and dentist Frank A. Evans had offices in the building. Other tenants were realtors Christopher C. Lipscombe, Robert M. Whitted, and Alonzo L. McCoy, hairdresser Ella Burnette, and the Lawrence School of Beauty Culture, operated by Cordelia W. Stewart.

Today, the building located on the corner of Wilson Alley, houses Limones and En La Calle.

The Old Post office

Built in 1892, the large brick post office was located in what is now Pritchard Park. It was torn down in 1932, when a new Post Office was built on Otis Street.

The Medical Building

16-18 College Street, Asheville.

Built circa 1898 and designed by Richard Sharp Smith, The Medical Building was built as a professional space for the Coxe Estate on what was then Government Street.

Today it is the Parsec financial building, next to Tupelo Honey on College Street.

Asheville Municipal Building

The Asheville Municipal Building was built in 1924 by architect Ronald Greene and contractor James Vester Miller. A plaque commemorating Miller on the side of the municipal building was dedicated July 27th, 2017.

These are the buildings that Miller is known to have built. There are others that I wonder if he had a hand in building:

The Jackson Building, built in 1924, holds the record for the tallest building on the smallest lot (15 stories on a 27’x60′ lot). The architect for the Jackson Building was Ronald Greene, who was the architect for the former Stephens Lee High School, built in 1923. Samuel Isaac Bean, the main stonecutter of the Biltmore Estate, was also a stonecutter on the Jackson Building and the Asheville Municipal Building. Bean also worked on The Basilica of St. Lawrence, which was built from 1905-1909. Rafael Guastavino and Richard Sharp Smith, all of whom James Vester Miller worked with on other buildings, were the architects of the Basilica. Guastavino and Smith also helped build The Biltmore Estate in the 1890s, although there is no record of Miller working on that site.

Miller died in 1940 and is buried in Violet Hill Cemetary – established by Miller and his son Dr. Lee Otus in the 1930s on Hazel Mill Road. His wife Violet Agnus Jackson (November 1, 1864 – April 13, 1936) was buried there in 1936 after her death.

With the perspective of history, Miller’s accomplishments were extraordinary. Born a slave, his infancy and early childhood shadowed by the Civil War, he would have been between 5 and 7 years old when the war ended along with slavery, leaving destruction and near-impossible to bridge divisions in the country. His mother moved her and her children to Asheville, and as a single woman, she would have been denied most rights, including the right to own property, vote, to be educated, and to educate her children. One article mentions that Miller skipped school to hang out at construction sites, but school wasn’t an option for most children, especially black children, at this time. St. Matthias Church, then Trinity Chapel, did offer classes in literacy and religion in the basement beginning in 1870, but the first public school for black or white children in Asheville wasn’t established until 1888 when Miller was 20 years old.

And while the Civil War ended legal slavery, Black Codes were enacted across southern states, including North Carolina. One major component of the ‘black codes’ were strict vagrancy laws – if you were found unemployed (and black) you were charged with vagrancy and sent to a workhouse (jail) – another form of legal slavery. Many places in the south required special permits for blacks to work, adding another barrier to the already hard task of finding employment.

During this time, and up until laws were radically changed with the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, banks legally practiced what was called ‘Red-lining,’ refusing loans for businesses or homes to any person of color and in neighborhoods that were considered to be non-white. In the construction business competition for contracts is key, and like many business ventures, relationships and networking are vital to establishing fair paying contracts. With access to education and training extremely limited, and put in competition with whites and at the mercy of mostly white employers, getting hired and getting paid a fair wage was a struggle.

Miller did all this: established a successful business that trained and hired other blacks in the area, built and handled real estate ventures – at a time when banks legally refused to lend money for business or real estate purposes to minorities. It was also perfectly legal during this time to base pay and contracts on race, ethnicity, and sex. If an employer didn’t honor a legal agreement for pay, or didn’t pay at all, Miller would also have had limited legal means to pursue any justice.

James Vester Miller was one of Asheville’s most prominent and important builders. And thanks to the dedication of his kin, especially his great-grandaughter Andrea Clark, his name has not been forgotten. His hard work and dedication to his community and future generations show the impact a single person can make by persistently rising above his unfair circumstances, changing lives and landscapes within the city.

Resources:

Built to Last, By Suzannah Smith Miles for WNC Magazine March 2012 https://wncmagazine.com/feature/built_last_0

http://toto.lib.unca.edu/findingaids/mss/blackhigh/biography/miller_jv.htm

North Carolina Architects and Buildings: James Vester Miller: https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000627

When did you write this about JV Miller

Where did

You get the church photos

Hi Andrea! I worked on this post for around a year, finally publishing it in March 2020. The church photos are all photographs I took after researching the buildings. I had wanted to get in contact with you regarding any information you had but didn’t have your email. Please reach out to amymanikowski@gmail.com – Thank you!